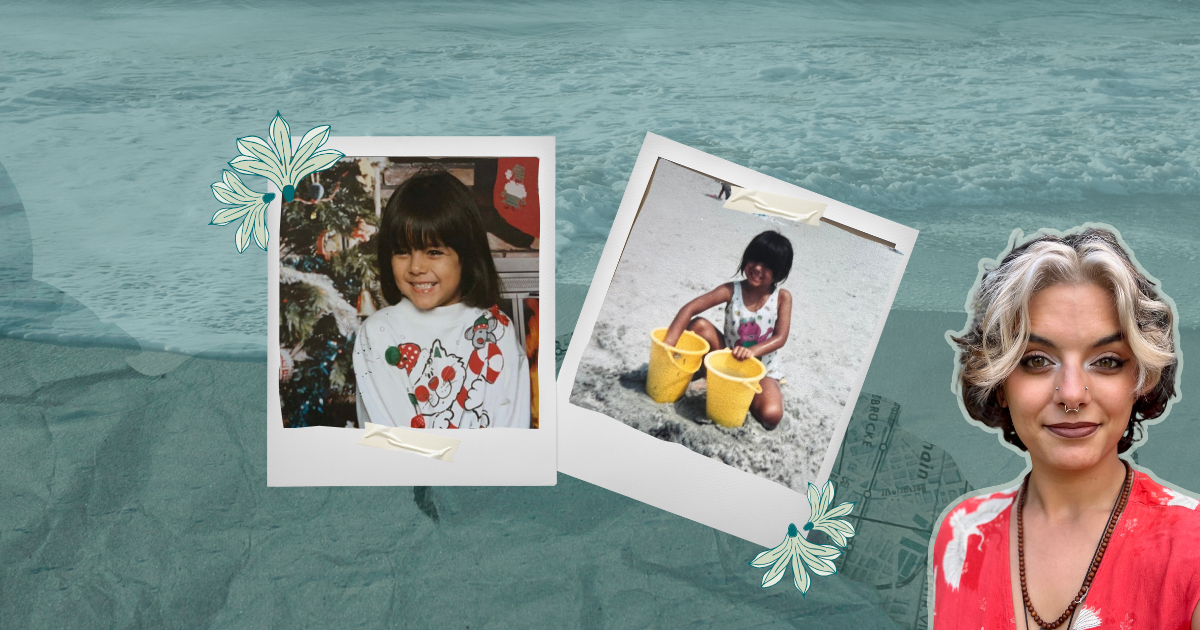

Written by Kūnaʻe Kamahele

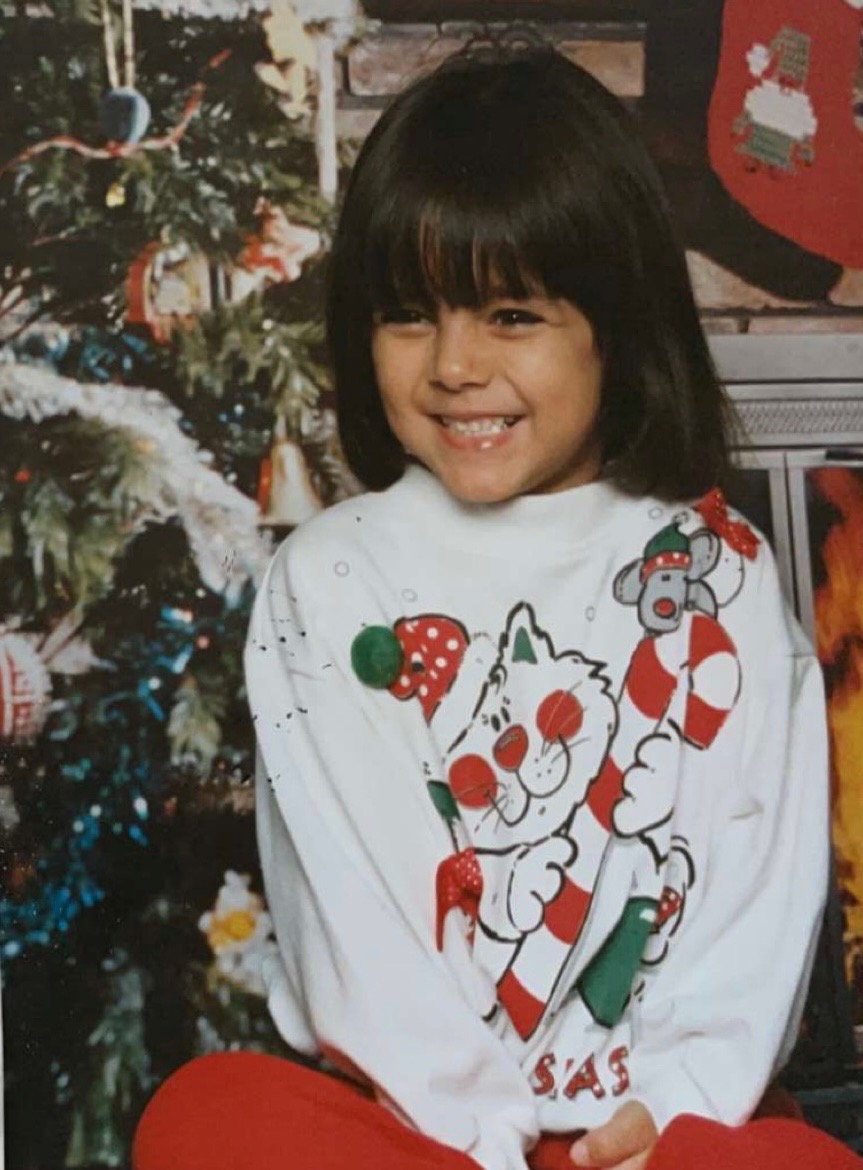

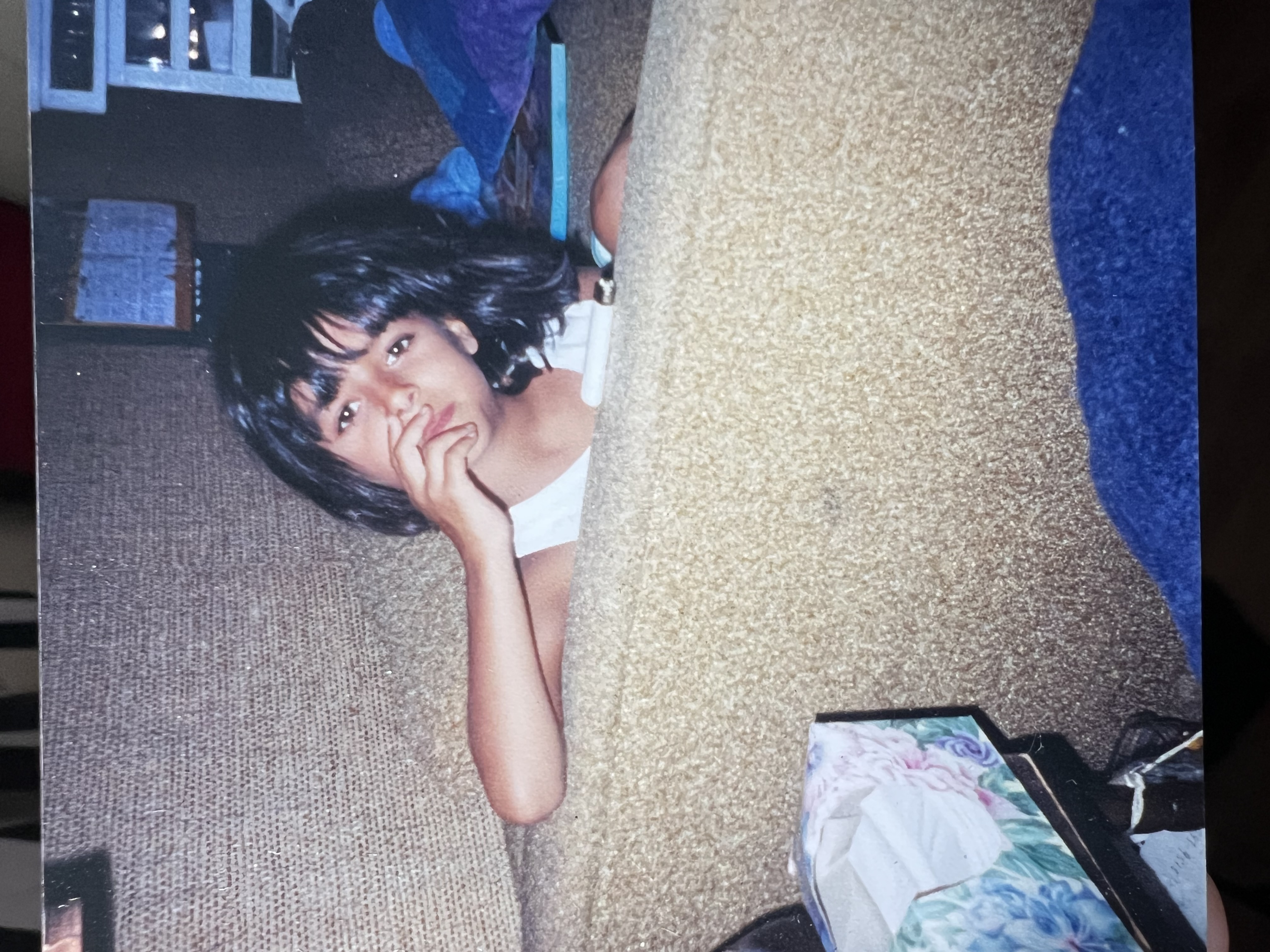

I was born in Pennsylvania to a Native Hawaiian father and a White mother. I was later adopted and raised by my biological mother’s White ex-husband, who was a single parent. According to my mother, the adoptive family didn't tell me I was adopted because it would be “too confusing” for a child–but it left me more confused as a mixed-race child in a predominantly white district.

I have vivid memories of fellow students asking me, “What are you?” and being called a liar when I told them I was White. This put me in a really awkward situation socially because some children thought I was intentionally lying about my ethnicity, which ended up isolating me further from my White peers.

Reflecting on my own story, I want to bring more attention to the larger Hawaiian adoptee experience and find others who can relate.

What role does adoption have in the journey of a generational diaspora Native Hawaiian (a person of Native Hawaiian heritage raised exclusively outside of Hawai’i)? I wonder about the overlap related to loss, rejection, and identity uncertainty. I also wonder–who else can relate? I know a few adoptees I’ve connected with online, but I haven't had a chance to get to know them well or learn more about their stories.

Truthfully, there’s a large puka (hole) in the visibility of adoptees and their experiences in Native Hawaiian communities, and little to no research on Native Hawaiian adoptees, where they are raised by their adoptive families, and the impact that has on an individual.

Many studies on adoptees group Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders together, and if one is of multiple ethnicities, they are in a completely separate group, just vaguely labeled “two or more races,” but the experiences of mixed individuals vary significantly based on their heritage and where they are raised.

It makes me think about the way I discovered I was adopted. Even that experience felt steeped in racial micro-aggressions. It was a friend of my adoptive grandmother who helped let the cat out of the bag. I'll never forget what she said as long as I live. She asked, “Did [my stepfather] marry a Colored woman?” And my adoptive grandmother replied, “No, she’s adopted.” And when I asked her to clarify what that meant, she brushed me off and ignored my question. I asked my mother about it and also learned I was legally documented as Caucasian because the judge overseeing my case had a reputation for denying mixed-race adoptions. Since sitting down to write this, I've learned that the Interethnic Placement Act (IEPA) was passed in 1996 to prevent adoptions from being denied on the grounds of race, ethnicity, or national origin, meaning the Judge who oversaw my adoption in 1998 wasn’t following the new updated laws.

In 2018, 251,980 children entered foster care in the United States, with 763 identified as NHPI. Of that 763, almost 70% were removed from their homes because of neglect which is defined as “Alleged or substantiated negligent treatment or maltreatment, including failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, or care,” by the US Administration of Children and Families Regulation (per this study: Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander children in foster care: A descriptive study of an overlooked child welfare population ). Coincidentally, NHPI families are also among the most impoverished in the nation, and this vague definition of neglect could also be applied to families who are struggling below the poverty line.

In 2008, Hawaiʻi legislators proposed the Native Hawaiian Child Welfare Act to allow Nā Kūpuna Tribunal to manage custody cases and placement for Native Hawaiian Children. However, the bill died during the legislative session, leaving fostering and adoption of Native Hawaiian children in the hands of state and federal agencies, with little consideration of the importance of Hawaiian culture and traditions.

“In Hawaii, the state routinely takes children away from families without a court order, despite federal court decisions making it clear that this should only be done in cases in which the child is likely to be harmed in the time it takes to go before a judge. Hawaii also has one of the highest rates among the states of returning children to parents within 30 days, which experts say is an indication that removal might not have been needed in the first place.” Anita Hofschneider, from the Article "Racial Disparities Vex Hawaii’s Child Welfare System. Can They Be Fixed?"

Adoptees often navigate experiences related to loss, rejection, shame and guilt, grief, and uncertainty of identity.

I had fuzzy memories from when I was four years old of lawyers and court houses and a judge asking me questions about my stepfather, but until my mom disclosed my adoption at the age of 11, I thought they were my imagination. Many people ask if I was upset or angry when I found out, but what I felt was a sense of clarity, and the questions from my peers made sense for the first time.

And the reality is that the adoptee experience for a Native Hawaiian can greatly affect their sense of self and identity.

I still didn't know what it meant to be Hawaiian as I had no Hawaiian family members around me, and that would remain true until I created a TikTok during COVID lockdown (@ThirdCultureKanaka) and visited Hawai'i for the first time at 27 years old. It’s largely thanks to my digital community on TikTok that I found resources to learn more about Hawaiian culture and history, and I often tell my friends and family that I wouldn't be here in Hawai'i without that support.

There is also the glaring fact that Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) are not protected by the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), and potential families are not required to have any connection to Hawai'i or the culture. ICWA is designed to ensure American Indian and Alaskan Native (AI/AN) children, if removed from their biological families, are placed in foster or adoptive homes that “reflect the unique values of Indian cultures,” (25 U.S. C. 1902) https://www.bia.gov/bia/ois/dhs/icwa

So, how can we help Native Hawaiian adoptees to better connect with their heritage?

But we can start by recognizing the complexity of the Native Hawaiian adoptee experience, including ones like mine. I hope to connect with other Native Hawaiian adoptees so we can better support one another. Those who might feel that sense of shame or guilt. By finding each other and connecting, we can learn more about our shared struggles in reconnection and what resources we need, and bring more attention to the tens of thousands of Hawaiian adoptees who are largely invisible in the Child Welfare System.

About Kūna'e

Kūnaʻe Kamahele is a Native Hawaiian designer and stylist originally from Pennsylvania, and a graduate of University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa with a degree in Hawaiian Studies and a minor in Anthropology. She serves as Hawaiian Diaspora’s Hawaiʻi Lāhui Liaison, supporting returning Hawaiians through community connection, peer support, and relationship-building with Hawaiʻi-based organizations. Grounded in lived generational diaspora experience and research in Hawaiian color psychology, Kūnaʻe brings care, cultural depth, and intentionality to all aspects of her creative and community work at Hawaiian Diaspora.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

There is very little information on the lived experiences of Native Hawaiian adoptees in the diaspora. Your responses will help Hawaiian Diaspora tell stories that are often missing, and help us better understand needs, challenges, and pathways to care, culture, and community.

Your responses will be used by Hawaiian Diaspora in a non-identifying way to help make visible the experiences of Native Hawaiian adoptees outside of Hawaiʻi, including where adoptees live across the diaspora and what kinds of support may be most meaningful. This information will not be used for commercial purposes, government systems, or adoption agencies. Our intention is simply to listen, learn, and let future care-based efforts be shaped by Native Hawaiian adoptees in the diaspora themselves.